South Pole Lake

When the weather isn’t good enough to fly, it’s usually good enough to still do some work around South Pole. So we went a visited South Pole Lake today. My stuffed orca, Ice, thought she’d get to go swimming. Apparently, I forgot to tell her that the South Pole Lake is under 2700 m (approaching 2 miles) of ice.

The lake is actually pretty small. A few kilometers along and across, and about 30m deep. But it’s really cool for a whole bunch of reasons.

First, for glaciology, ice flows differently when on top of water than on top of bedrock or sediment. So we can learn about how ice flows from studying the differences as the ice flows onto, across, and off of the lake.

Second, the lake tells us that the bed is melting. That is, enough heat flows up from the earth’s mantle and crust to melt the base of the ice sheet. Many scientists used to think South Pole was frozen at the bed, but work led by Ben, part of our team, showed that the whole South Pole region is likely melting at the bed. This affects ice flow, but also informs physics experiments.

Third, the lake has lots of sediment below it. We have no idea what these sediments would tell us – which is why I’m going to encourage my colleagues to drill a sediment core in the lake. Maybe we can learn about fluctuations in the size of the East Antarctic ice sheet, and maybe we can learn about millions of years of Antarctic geologic history. Who knows? And the unknown is what excites me!

Fourth, there may be life in the lake. Probably not fish swimming around. But maybe extreme bacteria. Oxygen reaches the lake as the ice melts and releases the trapped gases, so it’s possible there would be a microbial community. Understanding how life might exist in a location like South Pole Lake offers insight into life on other planets.

Despite not being swimmable, South Pole Lake is a cool spot to be able to visit. Its weird to think about lakes existing under ice sheets, but there are actually lots of lakes all around Antarctica. There is a lot of work going into exploring them, and maybe South Pole Lake will get a drilling project soon.

Hercules Dome

The goal of this season to find where is best to drill an ice core at Hercules Dome. I wrote briefly before about the measurements we are making, but here I will explain what is special about the Hercules Dome region for a deep ice core.

We were not able to fly today because of weather. Basically lots of clouds such that our Twin Otter cannot land easily in the white-on-white. This weather has come up from the West Antarctic ice sheet. WAIS Divide – the location of my first visit to Antarctica where we drilled a 3400m deep ice core – also had flights too and from it cancelled this morning. That’s because most storm system that reach South Pole come inland on the Amundsen Sea coast, up to WAIS Divide, onto Herc Dome, and begin to peter out at South Pole.

This storm pattern is what makes Herc Dome particularly interesting. Herc Dome is located between the East and West Antarctica ice sheets, with ice flowing in all directions. The snowfall at Herc Dome comes primarily from over the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. So Herc Dome “sees” changes in West Antarctica without actually being a part of it. This is important because a main goal of an ice core project is to understand how the West Antarctic Ice Sheet may have changed in the past.

The West Antarctic ice sheet has an ice volume equivalent to about 6 m of global sea level. If WAIS were to collapse, it would raise sea level by about 3 m. That’s because about half of the ice is already below sea level. All of the ice drilled at WAIS Divide when I was there was from below sea level. Having so much ice below sea level makes WAIS potentially unstable because there is a feedback loop – as ice retreats inland, if the bed gets deeper (more below sea level), then the ice flows faster. Then more ice is lost, it retreats to a deeper bed, and more ice is lost – until it collapses.

We don’t know if WAIS collapsed during a previous warm period – called the Last Interglacial – that was about 130,000 years ago. Some evidence suggests it did, some suggests it didn’t. So we want to figure out what the story with WAIS is. If it collapsed in a previous warm period, that’s big deal because 3m of sea level rise puts both my mom’s and my dad’s houses underwater.

Hercules Dome is the best place to drill an ice core to figure this out. As discussed above, it’s climate is influenced by the size of WAIS because the storms pass over it – but the ice wouldn’t go away if WAIS collapsed because it’s not part of WAIS. OK, I realize I may have lost some of you because this isn’t simple stuff – especially if you don’t think about Antarctica every day.

There are other goals of the ice core too, which I can write about more in the future. But for now, think of the Hercules Dome ice core as one of our best tools for figuring out how quickly sea levels change.

Field Work

Our field work plans took a big change this year. The US Antarctic Program has unique challenges in dealing with covid given the remoteness and lack of advanced medical care possible so far away from major cities. There was a two week pause on deployments, which went into place 2 days before we were set to depart. We eventually departed about 3 weeks late, but our season had been cut dramatically.

Instead of 30 days of camping, we are now doing 3 weeks of “day trips” to Herc Dome from South Pole. While a major cut, it is still an opportunity to do lots of cool science (and write blog posts with internet access :). Lots of projects have been affected this season, and in a way, we were lucky. We knew of our cuts before we left the US and have not had to pare down our season little bit after little bit.

We were able to start flying with the Twin Otter aircraft last Thursday and will have our last flying day on January 14. On Thursday, we were able to fly to Herc Dome – to an area called West Herc Dome, more on that in another post – with two flights. We took a snow machine (aka skidoo) on each flight, as well as a barrel of gas and some other equipment. So we are now set to start doing research on our next flight there.

On Friday, we flew to Herc Dome again, but a different location called East Herc Dome. This is where my team camped in the 2019/2020 season. They left a lot of stuff there, so we went to retrieve the most valuable items. In this case, it was a 600 lb groomer that gets towed behind a snow machine.

Weather is always a challenge for flights. You need good visibility to land on ungroomed snow surfaces. So we plan on only getting to fly 50% of the days that we are able to. This means that we hope to get 9 flights in the next three weeks. But it could be more, or it could be less. This makes planning a challenge.

Our goal for the next three weeks is to do a detailed survey of West Hercules Dome, which we didn’t get to do in 2019/2020 and is the most promising part of Herc Dome for an ice core. We have lots of other science objectives too, but the survey of this area is the most important. It’s a bit sad that so many scientific objectives won’t be accomplished this year, but on the other hand, it’s really exciting that we can go do any of this work. After two seasons of very little fieldwork, I feel lucky and privileged to have the support from the Antarctic Program to do as much as we can.

Twin Otter

Team digging out the groomer

Why am I here?

I haven’t written much yet about why I’m here. That is, what science I am working on. So here goes.

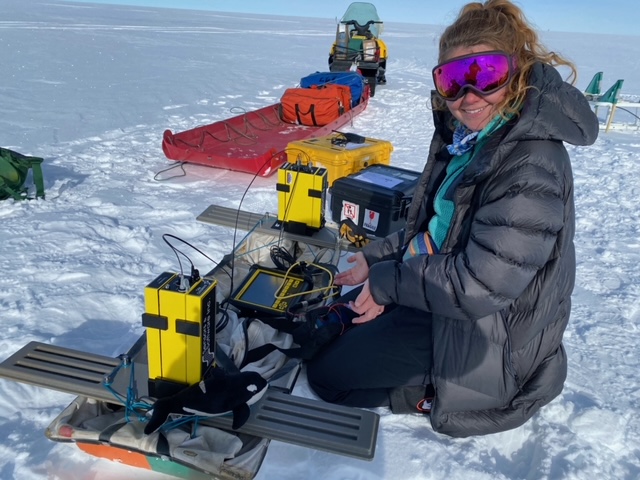

I am locating a site for a deep ice core project at Hercules Dome. Hercules Dome is at 86S, 105W, so it’s about 400 km from South Pole. We are using a Twin Otter plane to fly to Herc Dome to make ice-penetrating radar measurements. What is ice penetrating radar? You emit electromagnetic radiation from a transmitting antenna and you “listen” for what comes back on a receiving antenna. Basically, it’s a way to look at and through the ice.

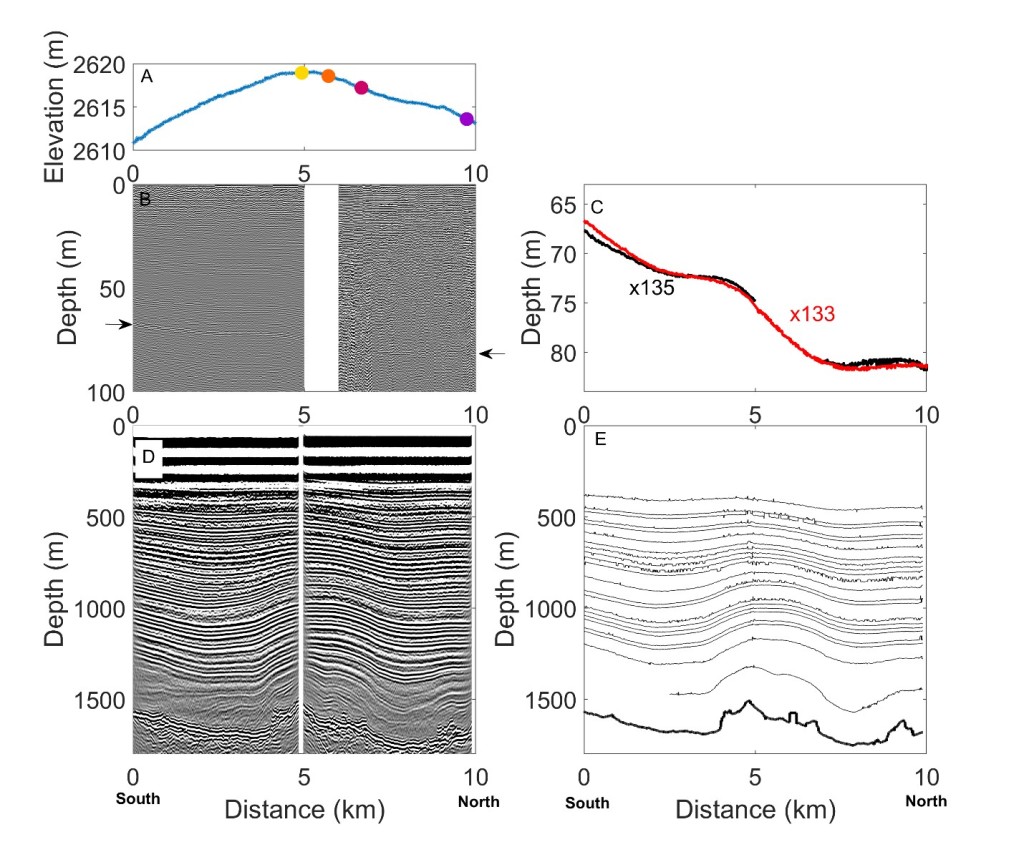

These radar measurements allow us to see a variety of things that we can’t just by looking at the surface. First, we can see the bed of the ice sheet, where ice meets the underlying rock. This usually forms the largest reflection of energy and tells us how thick the ice is.

Second, we can see internal layers in the ice sheet. These layers are caused by acids from volcanic eruptions that fall onto the ice sheet and form layers that are each of one age. The shape of these layers tells us about the past ice flow and whether there are any disturbances that would prevent a continuous climate record from being recovered. The layers near the surface can be used to figure out how much it snows each year. At Herc Dome, is snow between 11 an 15 cm per year of ice equivalent, or about 30-40 cm per year of snow. This isn’t that much compared to Washington Cascades, but it is relatively high for deep ice coring projects in Antarctica.

Third, we can use radars to measure the vertical ice flow. This is a relatively new technique. It allows us to better estimate how old the ice is with depth. These same radars can also tell us something about how ice crystals are oriented because the radar waves travel faster along some axes of the crystals compared to others.

I use all of this information in an ice flow model. I use the model to try and match the internal layers as best I can with what I know about how the ice flows. The models are never a perfect match because we don’t know exactly how ice deforms or how much it snowed in the past, but we do gain information and confidence in our interpretations by using the models.

I write more later about our progress once we get some new measurements from Herc Dome.

The Poles

We are celebrating Christmas with a two-day weekend – what Jessie would call a golden weekend during med school. The Antarctic work schedule is 6 days a week, with Sunday off.

I went for a cross country ski today. I couldn’t find skate skis, so I went with fish-scale classic skis. At the end of my ski, I stopped by the two Poles. It was my first visit to them this season. Some of you may be thinking the two poles are the geographic and magnetic poles, but no. We are nowhere near the South magnetic pole. Instead, we have a ceremonial pole in addition to the geographic pole.

Why the two? Well, it’s mostly because the ice at the South Pole flows.

The ice sheet here is roughly 2850m thick. It is moving at about 30 ft per year in a direction that is North! (OK, that joke it getting old). It is flowing what we all grid Northwest, with grid indicating the map projection we use such that north is up, south is down, east is east is right, and west is left. This means that geographic pole, which is fixed in space, is not fixed relative to the station and other structures. Since the station is our main reference point, it appears that the geographic pole moves, but in reality it is the station that is moving. There is actually a ceremony each New Year’s Day where the geographic pole marker is moved, so more on that in a week.

Back to the ceremonial pole. It is set right in front of the station and is surrounded by the flags of the nations that signed the inaugural Antarctic treaty. Many more countries have signed since. The ceremonial pole is quite picturesque. The geographic pole is less picturesque because it ends up at different locations within the station area. It currently is pretty close to the vehicle maintenance facility. Pretty cool, but not great for tourist pictures.

Merry Christmas!

T.J.

Flight to the South Pole

We arrived at the South Pole a couple of days ago. The day started a bit ominously. The winds were fairly high and clouds pretty low in McMurdo. Everything was going smoothly, we boarded the Herc and strapped in. They turned the engine on. And then they told us to deboard the plane as soon as the engines stopped.

Once off the plane, we watched about 10 Air National Guard people inspect the engine with the rumor being that they say some ice fly in or out. We went back to the galley to wait for more of an update. After about half an hour, they told us we were delayed 3 hours. The clouds got lower, some snow fell. And the Air National Guard were having some conversations on the phone that did not sound good. We opened computers and pulled out cards games, getting ready for a long stay and trip back to McMurdo.

And then after about 30 more minutes we were told to go the bathroom and get ready to board. Within 20 minutes, we were back out boarding the Herc. And we were off.

The weather was cloudy for the first hour of the flight, but as soon as we reached the Transantarctic Mountains, the clouds cleared and the views were spectacular. Mountains peaks poking out of massive glaciers. Huge crevasse fields and arcing moraines. Since I primarily work in the flat, white interior of the ice sheets – where it’s good to drill ice cores – I’m always fascinated by the more active areas where the signs of flowing ice are all around.

We landed a South Pole and hopped off the plane only a few hundred feet from the station entrance. But that walk is more exhausting than you’d think because you’ve just flown from sea level to 9300 ft, which feels more like 11,000 since there is less atmosphere at the poles. We are currently acclimatizing to the altitude as the field season has officially begun.

McMurdo

McMurdo is the main US station in Antarctica and also the largest station in all of Antarctica. It is in a beautiful location with an active volcano only tens of miles away and a gorgeous view across to a mountain range. The sea ice (frozen sea water) meets an ice shelf (a glacier that flows out over the sea water) and seals and penguins come in the summer.

McMurdo is not, however, a particularly pretty station. It has dirt roads, a hodgepodge of buildings, and lots of stuff – there are containers and depots all around.

What McMurdo may lack in aesthetics, it makes up for with function. Everything has to be brought in. Food, fuel, machines, building materials, basically every little thing. So much of the effort at McMurdo goes into moving cargo around. A ship comes in late summer each year – when the sea ice is at a minimum – and drops off lots of the basic stuff needed for sustaining life – from mattresses to wrenches. It may not be that pretty to look at, but it is vital. No science gets done until we know we can survive in the often harsh climate, so the most important roles are often the ones that get overlooked – running a generator, fixing a bulldozer engine, or treating the waste water.

Some things change, some things stay the same

It’s now been 12 years since the first time I came to Antarctica. It’s been fun to think through what things have changed, and what hasn’t. I’m going to focus on the stations and save the discussion of the environmental change for another time.

McMurdo is currently in the midst of a major construction project. Old dorms are being knocked down, while existing buildings are being added onto. You can watch construction via the live webcam here.

But for the most part, not much has changed. Most of the buildings are the same as they were 12 years ago. The galley is the same, right down to the Frosty Boy soft serve machine which works most nights.

We have gotten improved internet. On my first visit we were issued usap.gov email accounts because programs like gmail wouldn’t consistently load. Now, gmail isn’t horrendously slow and we can even do some texting on our phones.

One thing that has changed, although it can be hard to see, is that more and more equipment and material is being moved by traverse vehicles. This is particularly important for supplying South Pole station. They were testing out a traverse from McMurdo to South Pole 12 years ago, but now there are three traverses a summer which bring most of the fuel as well as a lot of other stuff, up to Pole. This saves a lot of plane flights, which frees them up for field science rather than station resupply. This is critical for my Hercules Dome and COLDEX projects (more on those later). I just ran into Dean, who I first met at WAIS Divide and is now leading the South Pole traverse.

So, with both infrastructure and people, some things change while some stay the same.

I made it!

I have made it to McMurdo!

It’s my first time here in 8 years and the feeling stepping off the plane is incredible.

It’s really hard to describe, particularly to my kids, so I’ve brought a friend along. This is Ice. She looks kind of like the Hercules C-130 that took me from Christchurch, NZ to McMurdo. Her friends Orcy and Blizzard stayed with Olivia and Adrian. Ice likes to get into everything, and is a bit of a pain-in-the-butt for a travel companion – but she is quite cute.

After seeing this photo, Adrian was curious how this plane landed on a icy, snowy continent. The runway for the plane is made of snow, but it has been compressed by heavy machines to make it really firm – close to solid ice but with a rough surface so the wheels don’t slide. Planes with skis can also land on it.

Jessie was a medical doctor at McMurdo in the 2010-2011 season, so one of the first places I visit when in McMurdo is the medical penguin. I hope to find some living penguins, but it’s a little early for them since the sea ice is still pretty thick and there isn’t much open water.

Olivia wants me to take a picture of Ice with a penguin. Jessie wants me to break the Antarctic Treaty and bring a penguin back 🙂